BLUF: Rapid motor decisions deteriorate with age. There is evidence that this occurs due to less capable processing of the task environment rather than physical weakness.

Aging affects everyone and it affects all aspects of our lives. On an individual level, our motor skills – the ability to control how our body moves physically – are a hallmark of our physical health throughout life and underpin our ability to perform many daily activities. We use these skills to interact with our environment and with others, for example whenever we bag groceries or catch a ball that’s been thrown to us. Unfortunately we know that our motor skills decline with age and that our quality of life is likely to decline hand-in-hand. Despite the importance of these skills for our daily life, there was a gap in our ability to reliably and quantitatively assess these skills in interactive settings.

Rapid Motor Decision Tasks

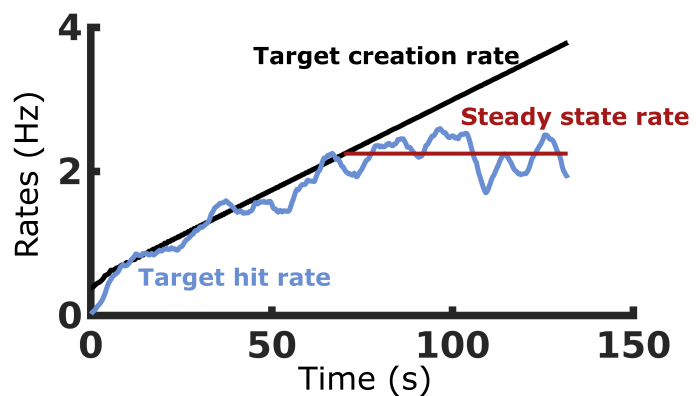

My co-authors and I investigated two interactive tasks that had initially been developed to quantify impairments after stroke, wondering if these tasks could also be used to assess changes in skill throughout the aging process. These tasks were named Object-Hit (OH) and Object-Hit-and-Avoid (OHA) and were both performed in a seated exoskeleton robot. Participants were told to hit virtual objects falling “down” the horizontal workspace in front of them both with (OHA) and without (OH) distractor objects indicated by different shapes. These objects would be created at a faster rate and with faster speeds throughout the tasks, ensuring that participants ended up by being overwhelmed by the task’s demands and requiring them to achieve their best performance. The position of both hands and all virtual objects were recorded throughout the trial by the robot, allowing both motor and cognitive parameters to be calculated.

Steady-State Rates

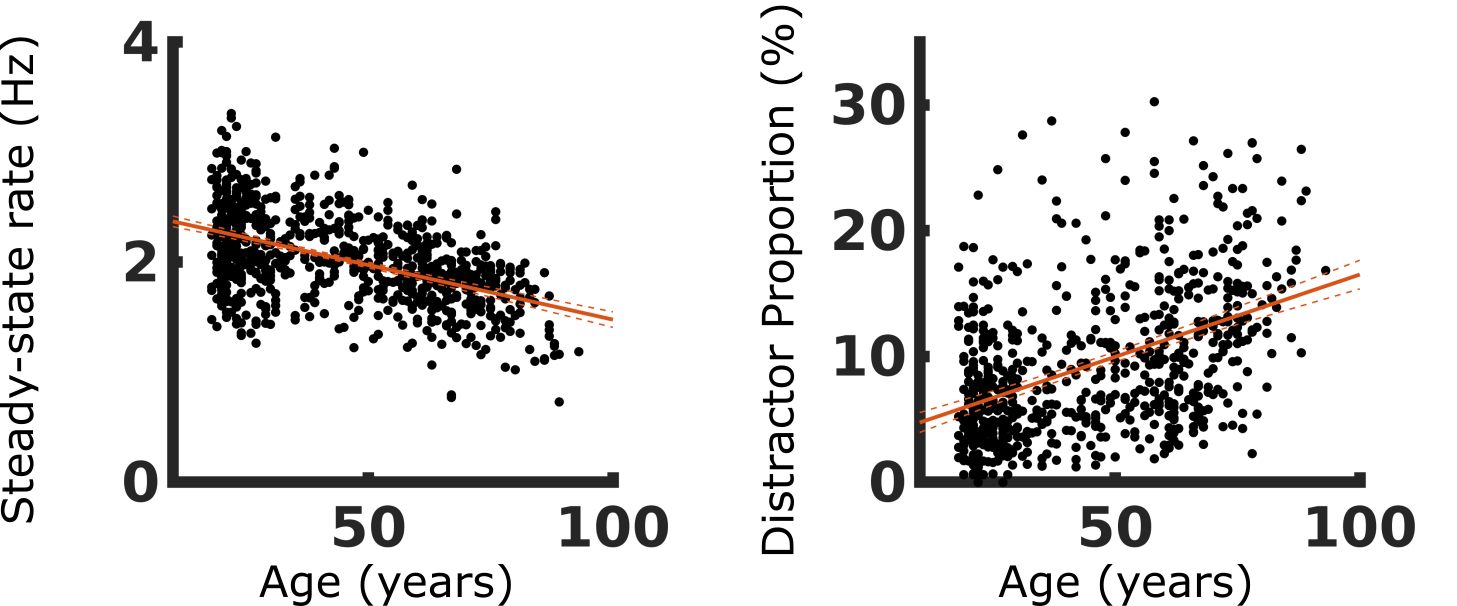

We assessed our two chosen tasks by using a database of 643 healthy participants whose ages ranged from 18 to 93, confirming that these tasks gave us parameters that reliably changed with age. Interestingly, we discovered that participants reliably reached a steady-state rate of hitting targets in both tasks at which point their ability to hit targets was saturated no matter how many more objects were available to be hit. We proposed that this steady-state rate could be used as a global measure of these kinds of interactive motor skills, summarizing many different facets of the human motor control system into one number.

Cognitive, Not Motor Declines

Having validated that OH and OHA could both measure useful parameters describing our participants’ performance, we followed up with a cross-sectional study where we examined the effect of age on these parameters. Unsurprisingly, older participants performed worse in both OH and OHA, hitting fewer targets with lower steady-state rates. Surprisingly, however, we were able to demonstrate that this decrease in performance is due to declines in cognitive and not motor abilities. For example, steady-state rates in both OH and OHA declined with age while the proportion of distractor objects hit during OHA increased, but measures such as hand speed and area of the workspace used by either paddle stayed relatively constant.

We also identified some older participants whose performance matched that of participants who were many decades younger, wondering if these individuals were examples of “super-agers” for whom aging seems to have a minimal effect.

Take-aways

The results of our study provided evidence that the OH and OHA tasks are useful for measuring some of the complex effects that aging has on our motor skills. We proposed that future work on neuropsychological tests could build on our findings and that our results could be useful to researchers seeking to understand human movement through the lens of embodied cognition.

Read the full paper here.